|

Vidya

and Avidya

Swami Vipashananda

The

terms vidya and avidya represent opposites.

Vidya refers to knowledge, learning, and to the different

sciences - ancient and modern. So avidya would mean the opposite

- ignorance, absence of learning, and illiteracy. Mahendranath

Gupta (M), the recorder of the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna,

was a graduate of the Calcutta University and served as headmaster

in several Calcutta schools. On his second visit to Dakshineswar,

Sri Ramakrishna asked him, 'Tell me, now, what kind of person

is your wife? Has she spiritual attributes [vidya shakti],

or is she under the power of avidya?' M replied. 'She is all

right. But I am afraid she is ignorant.' (1) That was a reply

typical of his times. He took vidya, as we still do, to mean

formal education. Later on M came to understand from Sri Ramakrishna

that 'to know God is vidya and not to know Him, avidya'. To

know about the world and worldly things falls within the domain

of avidya. This same interpretation is provided by the Upanishads

too.

Para

and Apara Vidya

In

the Mundaka Upanishad, a student reverentially questions

a rishi about Truth: 'Revered Sir, what is that by knowing

which everything (in this universe) becomes known?' (2) The

rishi begins his reply by classifying knowledge or vidya into

two categories: para (higher) and apara (lower).

Apara vidya refers to the four Vedas and the six accessories

of Vedic knowledge (the vedaigas): phonetics, the ritual

code, grammar, etymology, prosody, and astrology. The compass

is clearly very wide: the process of creation, the nature

of gods and goddesses and their relation to creation, the

nature of the soul and of God, the rituals that procure worldly

and heavenly enjoyments, and the way of release from the series

of birth and death; in short, religious or scriptural knowledge

and the ways of living prescribed by different religions are

all subsumed under apara vidya. Para vidya, the rishi informs

his student, is that 'by which the immutable Brahman (akshara)

is attained'. This Brahman is imperceptible, eternal, omnipresent,

imperishable, and the source of all beings. Scriptural study

is apara vidya, secondary knowledge. To know Brahman (or God)

directly and in a non-mediate fashion is the primary aim of

life, and is therefore termed para vidya.

If

the scriptures tell us about life, then what about the other

sciences - physical science and technology, and the social

and political sciences? They do play a very valuable role

in our lives, and are classed as apara vidya. But they are

secular sciences. What do we get through secular knowledge?

Wealth, power, luxury, and pleasure, but not the bliss that

results from spiritual knowledge. The apara vidya that comprises

scriptural knowledge helps us know that this world is not

the only world, that there are other divine worlds accessible

to human beings. The keeping of religious injunctions and

performance of scriptural activities are prescribed as means

for attaining enjoyment in these higher divine worlds. But

these gains are transient and ephemeral. However, if the obligatory

duties prescribed by one's faith are performed with the aim

of cultivating love of God and love of people of all faiths,

the performer gets his or her mind and heart purified, and

can attain the realization of that immutable Brahman which

secures eternal bliss.

The

Upanishads remind people with dogmatic and fanatic tendencies

that scriptural injunctions also lie in the domain of 'lower

knowledge'. The Mundaka Upanishadsays that people devoted

to mere scriptural ritualism are 'deluded fools': 'dwelling

in darkness, but wise in their own conceit and puffed up with

vain scholarship, [they] wander about, being afflicted by

many ills, like blind men led by the blind'. They think of

their way as the best and delude themselves into believing

that they have attained fulfilment, and so continue to suffer

the ills of life (1.2.8-10).

Ritual,

Knowledge, and Wisdom

The

Isha Upanishad makes the enigmatic statement: 'Into a

blind darkness they enter who are devoted to avidya (rituals);

but into a greater darkness they enter who engage in knowledge

alone.' (3) Here avidya refers to scriptural rituals. But

the term vidya is open to several interpretations.

It could mean mere theoretical knowledge of the scriptures

or meditation on various deities, which too has limited results.

Even the highest forms of meditation detract from the knowledge

that is para vidya, direct and immediate. A subsequent verse

(11) points out that harmonizing rituals with meditation leads

to the attainment of greater good-the relative immortality

consequent upon identification with a deity.

Which

the nisthe best way to wisdom? The second mantra of the same

Upanishad announces: 'If a person wishes to live a hundred

years on this earth, he should live performing action. For

a man such as you (who wants to live thus), there is no other

way than this, whereby work may not cling to you.' As an illustration

of this principle of work one may cite the diverse methods

used by Sri Ramakrishna to guide his disciples with varying

constitutions. He asked his disciple Girish to do whatever

he was doing but to surrender everything to the divine Will.

He instructed Narendranath on the non-dual Reality, knowing

him to be a fit subject for such instruction. In reality,

it is not work that binds but the mental attachment to work

and its fruits, the notion of doership and of enjoyment. Hence

selfless action, done in a spirit of service, is prescribed

by scriptures as sure means to the highest good.

What

is the best way to work and yet be free in this very life?

This is the subject of the first mantra of the Isha Upanishad:

"All this - whatsoever moves on earth - should be covered

by the Lord. Protect (the Self) through detachment (which

arises from this covering). Do not covet anyone's wealth."

The Shruti expressly states: 'all this'. Our usual notions

about 'I' and 'the world' (that both are real) are incorrect,

because these notions are changing continuously. Everything

in nature, including ourselves, is subject to death and destruction.

Even this earth, the stars, and galaxies are constantly undergoing

destruction and rebirth. This is an undeniable fact. So this

changing universe, and the 'I' therein, is to be covered with

the idea of divine permanence (that is, Brahman). With this

awareness that everything - I and the observed universe -

is nothing but Brahman, detached action becomes easier and

more natural. Enjoyment, which presupposes duality, is naturally

renounced if we become established in this idea. That is the

assertion of the rishis who have realized absolute Truth.

Not only do we then become unattached, but we actually love

this world as a manifestation of God. We then do our duties

to protect the world and do not covet anybody's wealth, for

this wealth too is God's.

Ignorance

and the Self

Sri

Ramakrishna says, 'The world consists of the illusory duality

of knowledge and ignorance. It contains knowledge and devotion,

and also attachment to "woman and gold"; righteousness

and unrighteousness; good and evil. But Brahman is unattached

to these. Good and evil apply to the jiva, the individual

soul, as do righteousness and unrighteousness; but Brahman

is not at all affected by them.' (4) The categorization of

'woman and gold' as avidya raises the inevitable question

(from a Brahmo devotee): 'Who is really bad, man or woman?'

Sri Ramakrishna answers, 'As there are women endowed with

vidyashakti, so also there are women with avidya shakti. A

woman endowed with spiritual attributes leads a man to God,

but a woman who is the embodiment of delusion makes him forget

God and drowns him in the ocean of worldliness. This universe

is created by the Mahamaya [the inscrutable Power of Illusion]

of God. Mahamaya contains both vidyamaya, the illusion of

knowledge, and avidyamaya, the illusion of ignorance.'

How

does one overcome avidyamaya? Through vidyamaya, for 'through

the help of vidyamaya one cultivates such virtues as the taste

for holy company, knowledge, devotion, love, and renunciation.'

Sri Ramakrishna further explicates the nature of avidyamaya:

'Avidyamaya consists of the five elements and the objects

of the five senses - form, flavour, smell, touch, and sound.

These make one forget God' (216).

Both

vidya and avidya are aspects of maya, the cosmic power of

Brahman. This power does not however affect Brahman (or Ishvara)

itself. For maya is under the control of Ishvara. But it is

by maya that human spiritual knowledge is covered. Again,

it is the vidya component of maya that is responsible for

the generation of spiritual knowledge, while avidya, even

as it covers spiritual knowledge, is the source of all secular

knowledge and human discoveries.

So

avidya is nothing but human ignorance about God's nature,

by which one is perpetually deluded into doing the rounds

of samsara, the cycle of transmigration. This avidya again

is nothing but misidentification of real knowledge, which

is one's real nature. Therefore, religious scriptures ask

humans to purify their heart, mind, intellect, and ego. Real

human nature is pure and divine; each soul is potentially

divine. Maya personifies our illusory perception. This phenomenal

world is the longest dream come out of cosmic mind, of which

the individual is a part.

'According

to the Advaita philosophy,' says Swami Vivekananda, 'there

is only one thing real in the universe, which it calls Brahman;

everything else is unreal, manifested and manufactured out

of Brahman by the power of Maya. To reach back to that Brahman

is our goal. We are, each one of us, that Brahman, that Reality,

plus this Maya. If we can get rid of this Maya or ignorance,

then we become what we really are.' (5) While lecturing on

'The Real Nature of Man' Swamiji dwelt upon the nature of

ignorance, avidya:

Ignorance

is the great mother of all misery, and the fundamental ignorance

is to think that the Infinite weeps and cries, that He is

finite. This is the basis of all ignorance that we, the

immortal, the ever pure, the perfect Spirit, think that

we are little minds, that we are little bodies; it is the

mother of all selfishness. As soon as I think that I am

a little body, I want to preserve it, to protect it, to

keep it nice, at the expense of other bodies; then you and

I become separate. As soon as this idea of separation comes,

it opens the door to all mischief and leads to all misery

(2.83). Swamiji also makes a distinction between objective

knowledge that is in the domain of avidya, and para vidya,

which is our very Self: 'Knowledge is a limitation, knowledge

is objectifying. He [the Atman, the Self] is the eternal

subject of everything, the eternal witness in this universe,

your own Self. Knowledge is, as it were, a lower step, a

degeneration. We are that eternal subject already; how can

we know it? It is the real nature of every man' (2.82).

Transcending

Maya

From

the above discussion it is apparent that both avidya and vidya

are forces, the two currents of one powerful Shakti, multiplied

into many currents. This fundamental energy, or Shakti, is

called maya, and is termed inscrutable because it is impossible

to characterize it in definitive terms. The epistemological

categories of knowledge and ignorance, as well as affective

attachment, are its components. Maya is Brahman as power.

The whole universe in its causal, subtle, and gross aspects,

and as perceived by the senses, is maya. From

the above discussion it is apparent that both avidya and vidya

are forces, the two currents of one powerful Shakti, multiplied

into many currents. This fundamental energy, or Shakti, is

called maya, and is termed inscrutable because it is impossible

to characterize it in definitive terms. The epistemological

categories of knowledge and ignorance, as well as affective

attachment, are its components. Maya is Brahman as power.

The whole universe in its causal, subtle, and gross aspects,

and as perceived by the senses, is maya.

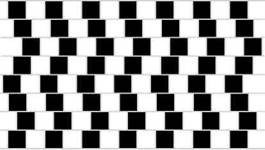

Horizontal lines are parallel

Avidya

does not always mean absence of vidya or knowledge. It also

has creative or projective components that make for the cosmic

abstractions of illusion, delusion, and confusion. In classical

Vedantic terminology avidya has two forces: avarayashakti

or the power of obstructing knowledge or consciousness, and

vikshepa shakti, the projection of individuality or ego Similarly,

vidya does not refer merely to epistemologically valid knowledge

- perception, inference, scriptural testimony, and the like

- but also to spiritual knowledge derived from intuition.

Avidya

refers to a state of confusion, delusion, and illusion: no

rational being would like to remain in such a state. Every

human being would surely like to transcend this state. True

But how? One cannot transcend it by a mere wish. Attempting

to rid oneself of maya while still in it is kin to trying

to lift oneself by one's own bootstraps. Therefore, Sri Krishna

tells Arjuna in the Bhagvadgita: 'This divine maya of mine,

consisting of the gunas, is hard to overcome. Those who take

refuge in me alone cross over this maya.' (6) Here submission

to the divine implies not only devotion to the transcendent

Reality, but also surrender of the ego, the key component

of avidya. Sri Krishna says further: 'Ishvara resides in the

hearts of all beings, causing them to move like puppets through

maya. Take refuge in Him alone with all your soul, O Bharata;

by His grace will you gain supreme peace and the everlasting

abode' (18.61-2).

As

noted earlier, vidya has two components: apara and para. The

former consists of words, sentences, and their meaning. Therefore,

it is essentially word-power. It urges the human mind to activity.

It functions not only on mental and intellectual levels, but

also on the spiritual level. On the latter plane it comprises

the spiritual power of persons who have experienced spiritual

truths: such persons are called rishis, seers. That is how

the scriptures of all religions retain the potential for transmission

of spirituality. When a person utters, 'Blessed are the pure

in heart, for they shall see God' or 'tat-tvam-asi; That thou

art' or ' aham brahmasmi; I am Brahman', these entences act

to remove the ignorance covering the spiritual insight of

the receptive heart. On the other hand, it is also through

the power of apara vidya that people start riots, crusades,

and wars in the name of religion. Therefore, true religion

lies in the transcendence of apara vidya. That is the goal

of human life. As

noted earlier, vidya has two components: apara and para. The

former consists of words, sentences, and their meaning. Therefore,

it is essentially word-power. It urges the human mind to activity.

It functions not only on mental and intellectual levels, but

also on the spiritual level. On the latter plane it comprises

the spiritual power of persons who have experienced spiritual

truths: such persons are called rishis, seers. That is how

the scriptures of all religions retain the potential for transmission

of spirituality. When a person utters, 'Blessed are the pure

in heart, for they shall see God' or 'tat-tvam-asi; That thou

art' or ' aham brahmasmi; I am Brahman', these entences act

to remove the ignorance covering the spiritual insight of

the receptive heart. On the other hand, it is also through

the power of apara vidya that people start riots, crusades,

and wars in the name of religion. Therefore, true religion

lies in the transcendence of apara vidya. That is the goal

of human life.

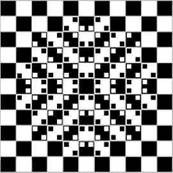

An illusory bulge

References

1.

M, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans. Swami Nikhilananda

(Chennai: Ramakrishna Math, 2002), 79-80.

2.

Mundaka Upanishad, 1.1.3.

3.

Isha Upanishad, 9.

4.

Gospel, 101-2.

5.

The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, 9 vols. (Calcutta:

Advaita Ashrama, 1-8, 1989; 9, 1997), 2.254.

6.

Bhagavadgita, 7.14.

|